Disrupted Foreshadows Silicon Valley Reckonings

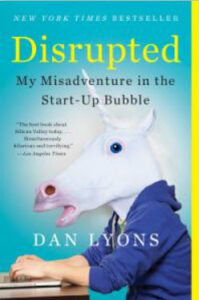

A Book Review of Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Start-Up Bubble by Dan Lyons

Review by Astrid Braun, Research Associate, Braun Ink

I’m home from college right now, and back with my second book review for Braun Ink—this time of Dan Lyons’ 2016 book Disrupted: My Misadventures in the Start-Up Bubble. This past summer, when she asked me to review the book, my mom pitched it to me as a funny account of Silicon Valley ageism. I found it to be more depressing than anything mostly as a result of all the other issues in the tech world that Lyons mentions. Looking back on his commentary from four years ago and seeing all of his concerns realized left me with a bad taste in my mouth.

I’m home from college right now, and back with my second book review for Braun Ink—this time of Dan Lyons’ 2016 book Disrupted: My Misadventures in the Start-Up Bubble. This past summer, when she asked me to review the book, my mom pitched it to me as a funny account of Silicon Valley ageism. I found it to be more depressing than anything mostly as a result of all the other issues in the tech world that Lyons mentions. Looking back on his commentary from four years ago and seeing all of his concerns realized left me with a bad taste in my mouth.

Lyons, a journalist in his 50s, is abruptly cut from his job as a Newsweek technology writer, and instead of searching for a position in the flailing journalism industry he decides to try his hand at marketing. And for a technology buff, where else is better than HubSpot, a Silicon Valley startup that develops software products for marketing and sales?

It’s easy to see why Lyons was a hit with my mom. He’s a witty, acerbic 51-year-old journalist who’s infiltrating the tech bubble by joining a young, hip startup. His observations—the uniformity of employees in race, age, and socioeconomic status, for example—are amusingly frank. “The old tech industry was run by engineers and MBAs,” Lyons writes. The new bosses? Young, amoral college grads who, as he describes them, “watched The Social Network and its depiction of Mark Zuckerberg as a lying, thieving, backstabbing prick—and left the theater wanting to be just like that guy.” Nearly all of them, of course, wealthy white kids.

Lyons spends much of the book relaying observations of his workspace and colleagues—the nerf gun fights and beanbag chairs, and the frat bros who, just a few years out of college, are his bosses. He struggles to fit in, and right off the bat his experience and expertise are ignored. Lyons is quite caustic in his criticism of HubSpot, which can make it difficult at times to discern whether he’s disliked because of his age, or because he doesn’t seem all that likeable. All the same, he paints a picture of a work environment built on college-age amusements and mushy rhetoric (HubSpot’s marketing tools are “making the world a better place”) that seems pretty ridiculous.

At times, Lyons interrupts his narration to examine the various issues he sees in Silicon Valley. He witnesses the tech world’s exaltation of greed; the superimposing of a noble “mission” on said greed; and the over-the-top demands on employees with little significant reward (the mission is rewarding enough!). He also outlines the economic structure of Silicon Valley. He deftly explains the economic workings of the tech bubble, the gamble people take in working in the bubble, and the information-gathering nature of the market.

In many ways, reading Disrupted in 2020 feels redundant. Lyons was witnessing a naïve Silicon Valley that deluded itself into thinking that all its new technology would make the world a better place, and led everyone else into the same fantasy world. Now, those same optimists are backpedaling. In 2013, tech executives knew the effects their products would have on kids. Now, everyone knows. Distrust of information collection is creating problems for social media business models. Antitrust cases are being brought against the dominant tech giants. And ire from both liberals and conservatives is being levelled at platforms for their algorithms and practices around free speech. Whether this pushback has any effect is yet to be seen.

While it’s interesting to look back at an insider’s concerns in 2016, and evaluate the extent to which they were warranted, most of those concerns are, by now, old news. When it comes to ageism in Silicon Valley, however, Lyons highlights an issue that is less frequently discussed. The internet, social media, and digital marketing are all modern phenomena, and as such they are constantly connected with the youth who grew up immersed in the digital world. In my life, this tracks pretty well. My dad might be able to program the Wi-Fi router to limit the amount of time my 13-year-old brother spends on Xbox, but my brother can just as easily find 10 different ways to trick the router into giving him 24/7 access. But, assumptions against older employees can discount the fact that they, too, lived through the tech revolution. Although many 50-year-olds ignored Instagram, there are some who embraced it wholeheartedly. And Lyons, evidently, is one of these older tech enthusiasts. Their scarcity doesn’t justify assumptions made against them.

While it’s interesting to look back at an insider’s concerns in 2016, and evaluate the extent to which they were warranted, most of those concerns are, by now, old news. When it comes to ageism in Silicon Valley, however, Lyons highlights an issue that is less frequently discussed. The internet, social media, and digital marketing are all modern phenomena, and as such they are constantly connected with the youth who grew up immersed in the digital world. In my life, this tracks pretty well. My dad might be able to program the Wi-Fi router to limit the amount of time my 13-year-old brother spends on Xbox, but my brother can just as easily find 10 different ways to trick the router into giving him 24/7 access. But, assumptions against older employees can discount the fact that they, too, lived through the tech revolution. Although many 50-year-olds ignored Instagram, there are some who embraced it wholeheartedly. And Lyons, evidently, is one of these older tech enthusiasts. Their scarcity doesn’t justify assumptions made against them.

Lyons adeptly explores ageism in Silicon Valley—though that certainly isn’t what he set out to do with his job at HubSpot. But, ultimately, Disrupted didn’t really connect with me. Firstly, I’ll point out the obvious: I’m young, and this is a book that mostly makes fun of young people. I’m not personally offended by his remarks, but I think they probably land better with people of his generation.

Secondly, I found it hard, especially now, to be on board with Lyons’ foray into Silicon Valley in the first place. It’s clear early on that Lyons understands the exploitation of information and labor that is central to Silicon Valley’s success. And, after having had Instagram, Snapchat, and Vine in middle school, I quickly found that, well, I hated them. So, as a young person who dislikes such technology and the industry that produces it, I found it difficult to root for anyone wanting to enter that world. And, despite the unfortunate situation Lyons finds himself in, he walks away with solid HubSpot stock options, a top-notch job offer, and a spot writing for a TV show. Plus, he published a book about it all! It’s a bit hard to feel bad for the guy.

And finally, I just didn’t find Lyons very funny. Or perhaps I just found the subject matter to be more depressing than I had expected. The combination of the two resulted in my feeling that I spent 258 pages as a fly on the wall while a middle-aged white guy experiences exclusion for the first time. It’s not that the exclusion wasn’t real, or harmful. It’s just that there are so many other things on my mind.

- Braun Collection, Story & Biography Expertise