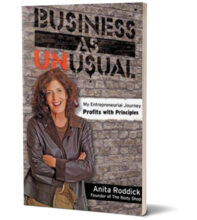

Business as Unusual Argues for Infusion of Personal Values in Capitalism

A Review of Business as Unusual by Anita Roddick

By Astrid Braun

Executive Summary: I recommend this book for anyone who wonders how they can enter or live in the business world and truly focus on building up the people around them.

While working for my mom in various roles this summer, one of my tasks was to read Anita Roddick’s 2005 executive memoir Business as Unusual: My Entrepreneurial Journey. My mom knows that it’s an older book, but she wanted me to review it in order to get a feel for the different forms of entrepreneurship storytelling. Older generations may know Roddick and her company, The Body Shop, but I am neither knowledgeable about great historical entrepreneurs nor interested in the world of cosmetics. I opened Roddick’s book expecting to learn a good deal about the inner workings of the cosmetics world and the woman who, according to the back cover, revolutionized it.

In my reading, I encountered less a story of the late British businesswoman’s life than a mapping out of her principles, developed over the 15 years she spent building The Body Shop. Roddick was a pioneer of what were considered to be radical business practices, advocating for political activism, fair trade, and sustainable products and packaging. All of the practices she implemented stemmed from personal values of equality, environmental preservation, and community. Her big push? Incorporate personal values into business.

Roddick admits early on that the personal values she holds seem to contradict those of a capitalist system: individualism, competition, materialism, and growth. She reconciles the two sets of values by encouraging readers to not see the contradiction as black and white. However, she doesn’t elaborate much further.

“If activism is profitable, companies will gladly partake. If not, then progressive values take a backseat.”

Throughout the book, it seems that Roddick is at odds with the businesspeople around her—they push a hierarchical business model, while she pushes for open-door policies across the board. They look at profits, while she looks at political causes. Roddick portrays this constant battle as the business establishment against the business revolutionary, and at times that can be the case. Her marketing ideas and pushes for environmental sustainability were new and, in fact, profitable. But the majority of the time, I interpreted the battle as that of an activist with businesspeople.

Roddick argues throughout the book that her concern was not profits. This worked out well for her when the activism focus at The Body Shop held a certain novelty for consumers and produced profits anyway. But in 2020, Amazon ad campaigns can tout support for Black Lives Matter and in the same breath sell technology, such as its Amazon Ring, which works closely with police departments and can encourage racial profiling. If Amazon followed through on the ideals that it claims to adopt, Jeff Bezos would not be approaching a net worth of $200 billion, and the company would not be the $2 trillion giant that it is today. Ultimately, in a market economy, sales win out. If activism is profitable, companies will gladly partake. If not, then progressive values take a backseat.

To me, the ultimate activism is the revolutionary practice of paying a living wage. In the past month, another task of mine has been to write a Braun Ink comic book case study about my dad’s leadership of the rustbelt-based family manufacturing firm, Custom Rubber Corp. In that time, I’ve had the opportunity to learn about the small business side of things, where global market competition is much more present than it might be for a giant like Amazon. My dad has talked about experiments in increasing wages for Custom Rubber employees, only to find that employee retention rates stay the same. He’s trying to implement Employee Assistance Programs, only to find the same thing. Ultimately, competition from other companies — domestic and international — forces him to focus on operations and profit.

“The omnipotence of business forces consumers to rely on business leaders like Roddick, who take risks in furthering the values of community and equality.”

At the onset of her memoir, Roddick establishes two important principles. The first is that business is more powerful than politics or religion; the second is that business, that all-powerful entity, must be regulated by political bodies. In this day and age, these principles still ring true. The omnipotence of business forces consumers to rely on business leaders like Roddick, who take risks in furthering the values of community and equality. Businesses that can afford to invest resources back into their communities may find that they reap the rewards. Even if the payoff isn’t monetary, true entrepreneurs know that there is an inevitable and intangible reward in building things up, instead of breaking them down.

- Story & Biography Expertise